For as long as there have been cities, there have been wanderers.

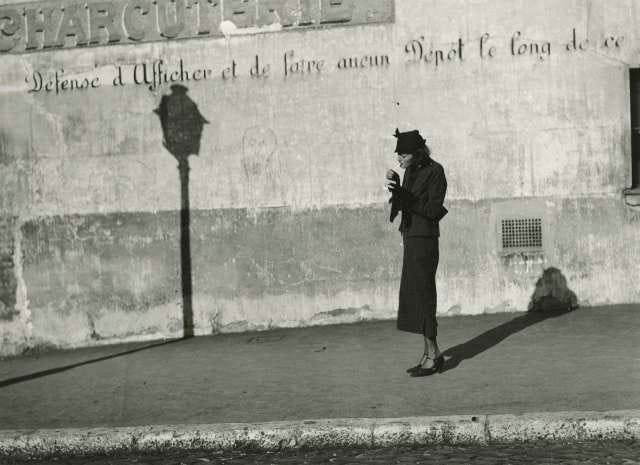

Typically, the flâneur was a privileged, masculine urban meanderer. One who had the leisure to stroll, observe, record, and reflect on his surroundings and the consequent intrinsic musings it led to. One who had the freedom to get lost to find something grander than oneself. Ultimately, giving rise to several artistic movements like psychogeography.

The flâneur was, as Charles Baudelaire wrote, “an ‘I’ with an insatiable appetite for the ‘non-I’.”

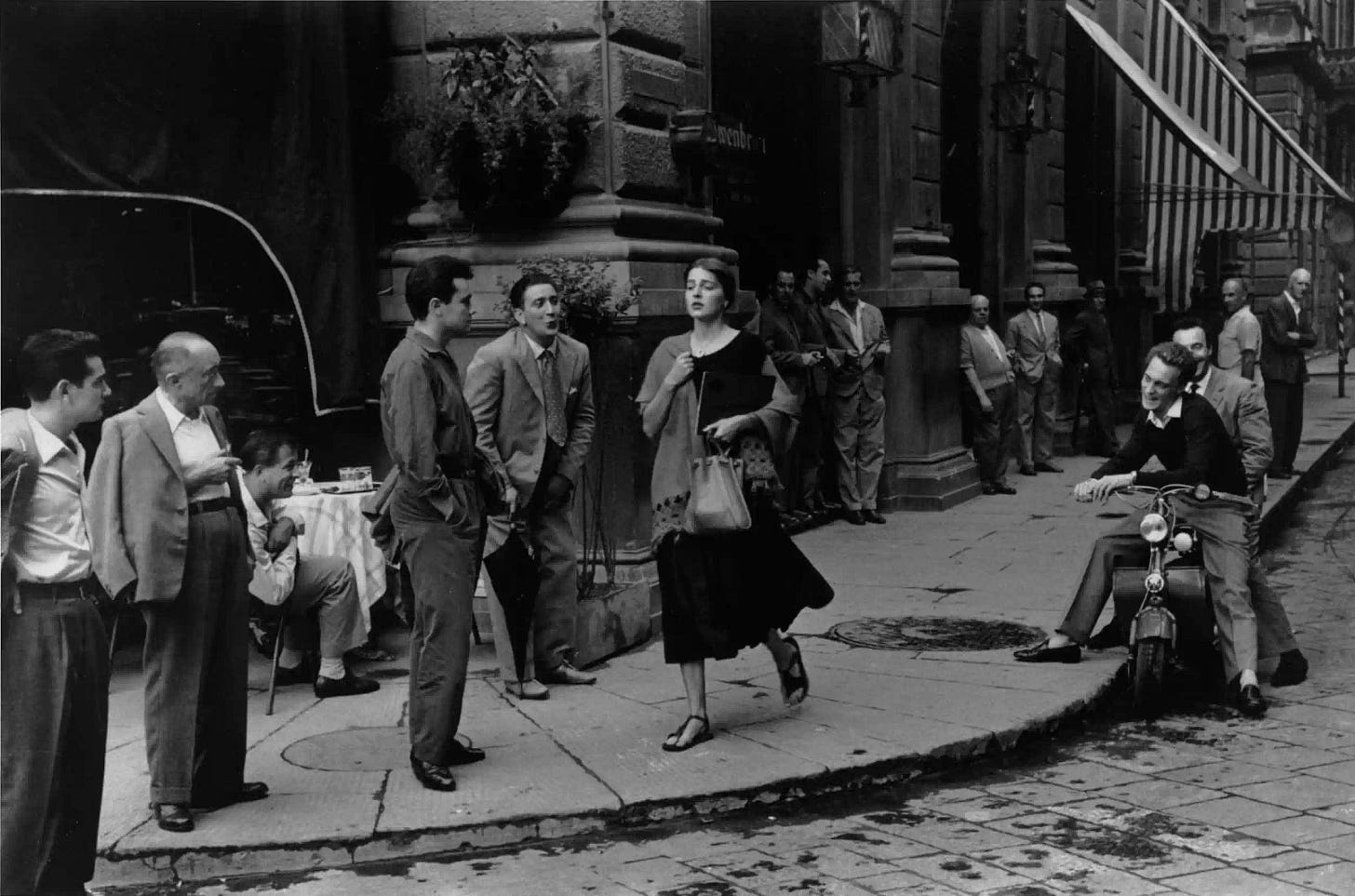

The ability to be an invisible observer was solely restricted to men. Women, due to safety and domesticity, haven’t had the same privilege to stroll wherever their inspiration may take them. Women continue to look over their shoulder, tend to stay in after dusk, and never traverse the road less travelled. Paradoxically, while women have never had the ability to be invisible in cityscapes, there were several that were engaging with city spaces who weren’t getting a lot of coverage.

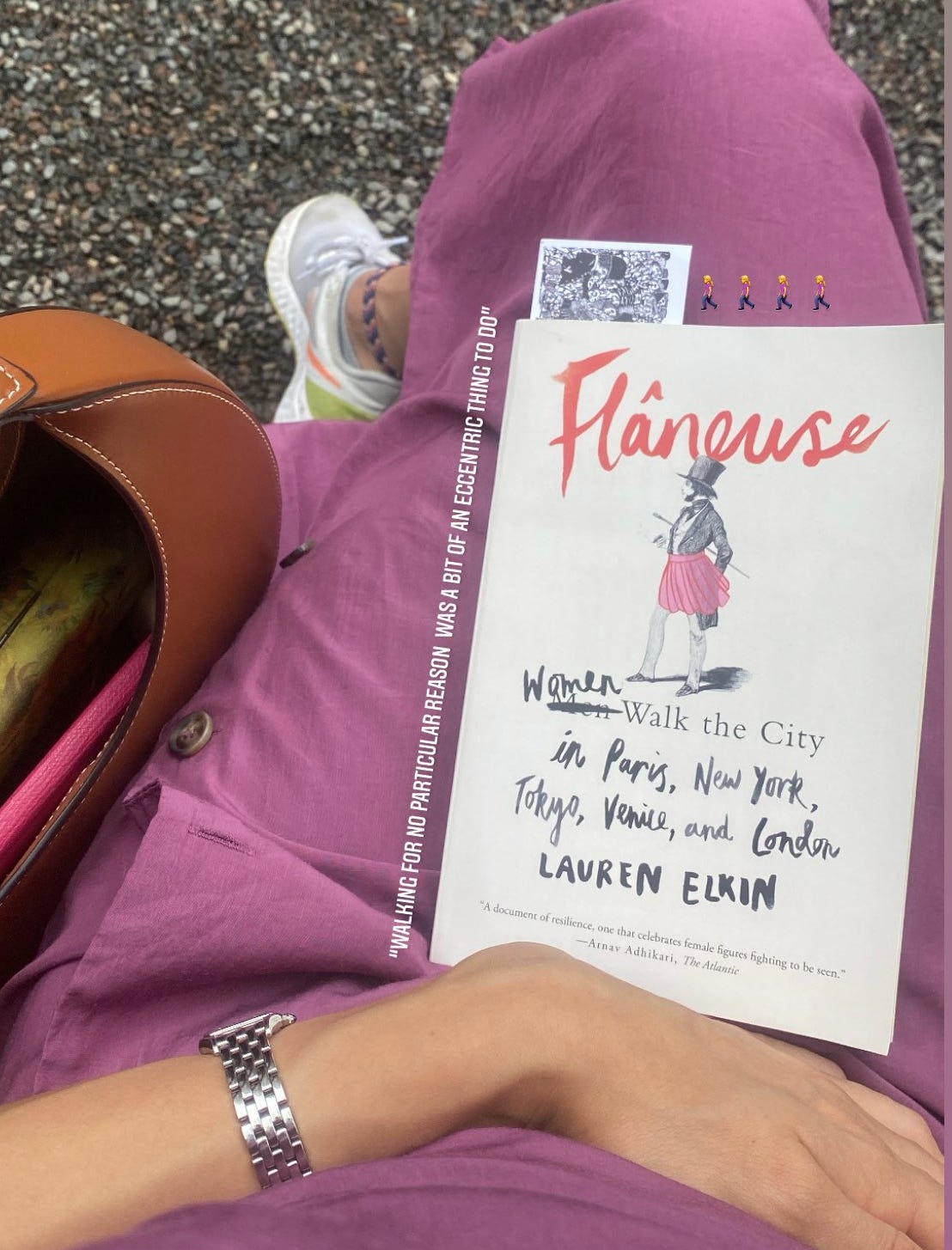

Lauren Elkin’s novel provides evidence to redefine the concept of the flâneur to include women. It reads like a stroll through snapshots of history. It is part memoir, literary criticism, and ode to seminal women (Virginia Woolf, George Sands, Jean Rhys, Joan Didion, Lauren Elkin herself). The book chronicles their lives in cities and how they’re reclaiming them through walking.

The women are asserting their will to be independent, to take up space, to explore, to create, and to demonstrate erudition.

Throughout history, women have been the subject instead of the creator of art. Women were not given the platform to speak or strut. Further, those that did had baser pleasures associated with them, like “streetwalker”. This is a reductive perspective. For Virginia Woolf, who had the idea for To the Lighthouse one afternoon while walking in Tavistock Square, there was a clear connection between walking and creativity.

Outside of creative expression, the book also questions the urban experience: are we individuals, or are we part of the crowd? Do we want to stand out, or blend in? Is it even an option? How do we – no matter who we are – want to be seen in public? Do we want to attract or escape the gaze?

I particularly loved how the book took into consideration that there exists a "female gaze" - one that is very aware of being perceived and is not invalidated by that. Especially now, as women think it to be empowering to photograph/film/represent themselves in any way they'd like, I think the book makes the case that the most empowering way to represent the female gaze is by demonstrating what she sees and her viewpoint and not how she looks.

What it means to observe and be an observer. What it means to be a creator versus creation of art.

Unfortunately, women still can’t walk in the city in the way a man can. Women continue to march in the city streets in defense of women’s rights, for control of a woman’s body, and where she goes or walks.

Regardless, the daunting act of flânerie - to have the conviction to wander - allows women to break shackles of expectations erroneously thrust upon them. It empowers them to assert their curiosity and to contribute to the urban experience.